Peatoniños: Street transformations for a safer Mexico City

Project Type: Urban intervention

My Role: Participatory Urban Designer

Methods: Contextual inquiry, field study, participant observation, surveys, interviews, participatory design workshops, communal mapping, traffic count

Location: Mexico City

Institutions: Laboratorio para la Ciudad (innovation wing of the Government of Mexico City)

Duration: 2018-2019

proJect DeScription

In the neighborhoods of Tepito and Iztapalapa, Mexico City a lack of green and open spaces as well as high crime rates make the streets hostile towards children, the most vulnerable population in the city. The Peatoniños project sought to redesign streets to be more amenable and safe for children. The project included extensive interaction and learning from the local community in order to design a space that met their needs.

My role was to develop and implement the survey and data gathering tools we used to understand community needs, and assist in leading group conversations with the neighborhood. In total, we created and put into action 8 participatory design activities in the transformation of an alleyway in Iztapalapa.

Key questions

How can we understand the array of experiences of the users of the streets?

What are the existing conditions and uses of the street?

What are the perceptions of the street?

How can we create a space that responds to the various needs of the neighborhood?

How can we ensure the long-term success of the project?

More information can be found here.

Process

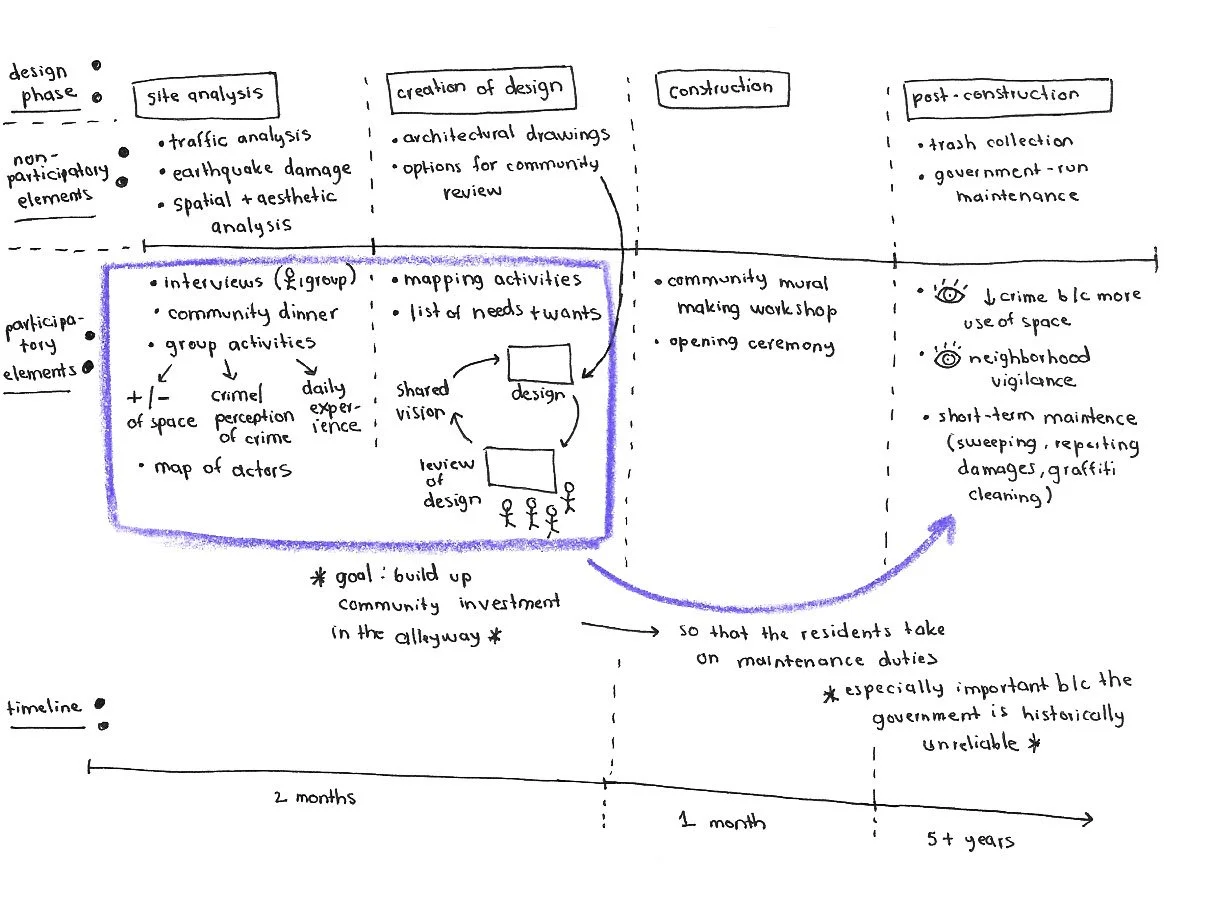

Our process included 8 design workshops with the neighborhood, each developed to learn about a specific aspect or perception of the street and create a shared vision for the transformation. We focused on the daily experience of adults and children, perceptions of safety, maintenance, traffic, and imagining futures for the street.

Our goal in using a participatory design process was to create a space that reflected the community and solved the infrastucture issues around lighting and water. Since the government does not maintain public space in the neighborhood where the project was based, it was also critical that the community cared enough about the project to preserve it in the long-term.

Project Photos

Learnings

Expect resistance and excitement, and be patient: Especially where there are complicated histories around governments’ and institutions’ treatment of residents, when beginning a participatory project residents will push back because of a lack of trust. They will also have a lot of ideas for how to improve their neighborhood. It may be necessary to lengthen community processes in order to build up trust–be patient.

Create a shared vision to guide the project: Often, not everyone will agree with a specific intervention, but rather on a shared vision for an urban space. For example, a plaza that feels safe at all hours of the day so that their children can enjoy it. This shared vision is a great basis for designers and architects to propose solutions.

Extrapolate user needs from proposed solutions: For example, if a resident (as in this project) asks for a security camera to be installed, it is not necessarily that the security camera is necessary but that increasing perception of safety or safety is. In any participatory process, it is important to understand the why behind user proposed solutions and requests to more deeply grasp their needs.